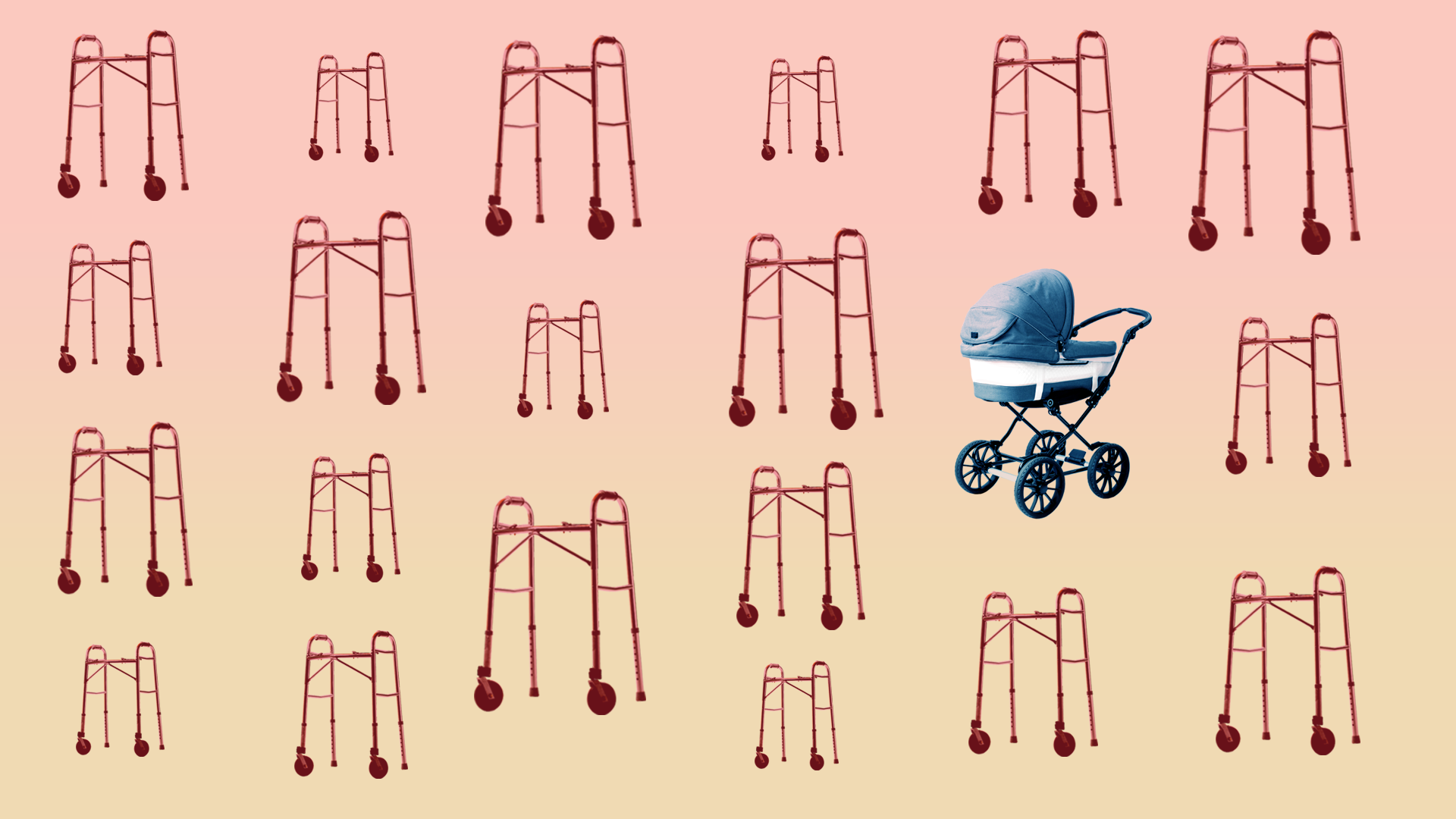

When children become scarce

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios

The future will have fewer children.

Why it matters: Across the advanced economies, the population of children is declining. With a shrinking pool of youth entering the work force, many fear that industrial economies like Japan's could teeter, with acute worker shortages and less tax income for social payments to the bulging elderly population.

The big picture: Nowhere are children scarcer than in Japan and South Korea, which have spent billions to raise their birth rates but have failed so far to halt the trend. But the demography is almost everywhere.

- "Shrinking fertility is a trend in most modern societies — in most of Europe and quite a bit of Asia. Japan’s just the leader," Mei Fong, author of "One Child," a book on China's one-child policy, tells Axios.

- The number of children on Earth younger than 15 will peak at 2.09 billion in 2057 and begin a decline, falling just under 2 billion by 2100, writes demographer Max Roser.

- The U.S. has record low fertility, Axios' Bob Herman reported earlier, falling to 3.94 million babies in 2016, about 37,000 fewer than 2015.

Be smart: The demographics are a hard inducement for aging advanced economies to embrace advances in robotics that can take the place of humans across industries.

- Japan's population of children has declined for 37 straight years, report CNN's Yoko Wakatsuki and James Griffiths. As of April 1, "children made up just 12.3% of [Japan's population], compared to 18.9% for the US, 16.8% for China, and 30.8% for India," CNN said.

- In South Korea, some experts call it a "birth strike," reports CBC's Kim Brunhuber.

- "Young people either don't marry, marry late, or don't have children," says Gi-Wook Shin, a professor at Stanford University, speaking with Axios. "The big question is what to do."

Countries have tried different solutions:

- Over the last decade, South Korea has spent about $70 billion in inducements such as free child care to encourage couples to have children, but to no avail. "Some say it's time to embrace migration like the U.S. and Canada. But many Koreans and Japanese are hesitant to embrace immigrants," Shin said.

- Scandinavian countries have tamped down the trend by "throwing a lot into social support networks and, as important, shoring up gender equity," says Fong. "Straightforward baby bonuses like what Japan’s offering don’t seem to work without gender equity."

That is one explanation for the boom in robots in Asia.

"If you can’t grow it or import it, the next step appears to be to make it, with robotics used not just in manufacturing but to meet the most pressing need — eldercare support."— Mei Fong

Go deeper: Read about "Peak Human," the possibility that the total global population could decline this century.