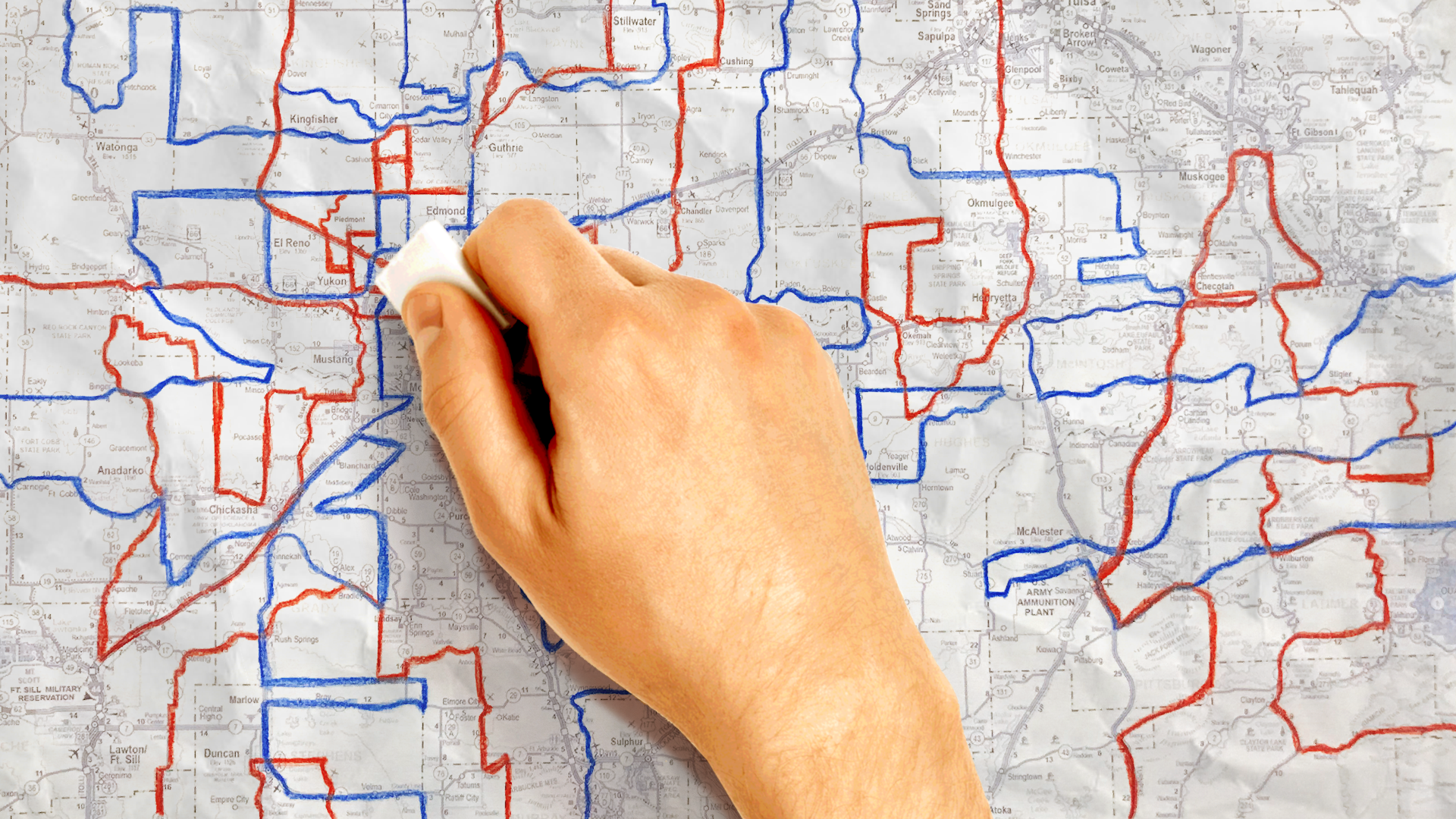

Gerrymandering's moment of reckoning

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

Illustration: Rebecca Zisser / Axios

Gerrymandering is at a tipping point. The courts are taking a harder line than ever before, saying some states have simply gone too far as they tried to give one political party an advantage. But if the Supreme Court doesn’t join the mounting legal backlash — and soon — there may be no limits on state parties’ ability to design their own political battlegrounds.

Why it matters: The outcome of these legal battles not only has the potential to upend the 2018 midterms, but also the more fundamental tools of politics and governance. If you’re trying to preserve a majority, gerrymandering works. The question is whether it works too well.

Where it stands: The dam has broken on partisan gerrymandering. After giving the states free rein for decades, federal courts recently struck down legislative maps in Wisconsin and North Carolina, drawing a constitutional line that had previously existed only in theory.

Pennsylvania's Supreme Court also ruled last week that the state’s Republican-led redistricting plan violated the state constitution.

- “This is a very different moment, in the sense that you now have a number of federal courts striking these plans down,” said Richard Pildes, an NYU law professor who specializes in issues that affect the democratic process.

- The momentum in lower courts has pushed the issue of partisan gerrymandering back to the Supreme Court. It heard oral arguments last year over Wisconsin’s gerrymandering and will hear a case this spring over one set of district lines in Maryland. A ruling against North Carolina’s partisan redistricting plan is also in the pipeline toward the high court.

What they’re saying: The legislatures that came up with these controversial district lines say this is all just part of the political process. That’s always been the Supreme Court’s position, too, at least in practice — and some of the court’s conservative justices seem inclined to keep it that way.

- “You're taking these issues away from democracy and you're throwing them into the courts pursuant to … sociological gobbledygook,” Chief Justice John Roberts said during arguments in Wisconsin’s case.

The other side: Critics say Wisconsin and North Carolina are examples of just how aggressive and sophisticated gerrymandering has gotten. And they say waiting for a political solution is a Catch-22 — you can change the redistricting process by winning elections, but the redistricting process makes it almost impossible for you to win elections.

- In Wisconsin, for example, Democrats won more than 50% of the vote in 2012, yet Republicans ended up with 60% of the state’s legislative seats.

How it could work: Academics have proposed a couple of tests the courts could apply to decide when a partisan gerrymander becomes unconstitutional.

- One possibility would be to look for “partisan symmetry” — the idea being that if, for example, Republicans winning 55% of the vote gives them 70% of the seats in the state legislature, that’s OK as long as Democrats would also control 70% of the seats if they won 55% of the vote.

- But that’s the “sociological gobbledygook” Roberts was worried about.

Why now: Republicans may be victims of their own success here. They dominated a majority of state governments after the 2010 census, when district lines had to be redrawn, and they maximized that advantage.

- Roberts has said he’s worried that if the court starts striking down some states’ maps, it’ll have to litigate every redistricting plan in the country, and will be perceived as partisan.

- The case from Maryland involves a Democratic-led gerrymander, and therefore might offer the court a way to tackle this issue without appearing to single out Republicans.

The impact: Even a limited ruling against Wisconsin, Maryland or (eventually) North Carolina would cross a new and unprecedented threshold.

On the other hand, the court’s past allowances that political gerrymandering could theoretically be unconstitutional may not matter if it can never identify an actual map that crosses the line.

The bottom line: This is a dispute the courts have tried to stay out of for years. “I think there might have been at some level some hope that other institutional solutions would emerge,” Pildes said. But it’ll be hard to stay neutral much longer.