The pitch for a health DARPA

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

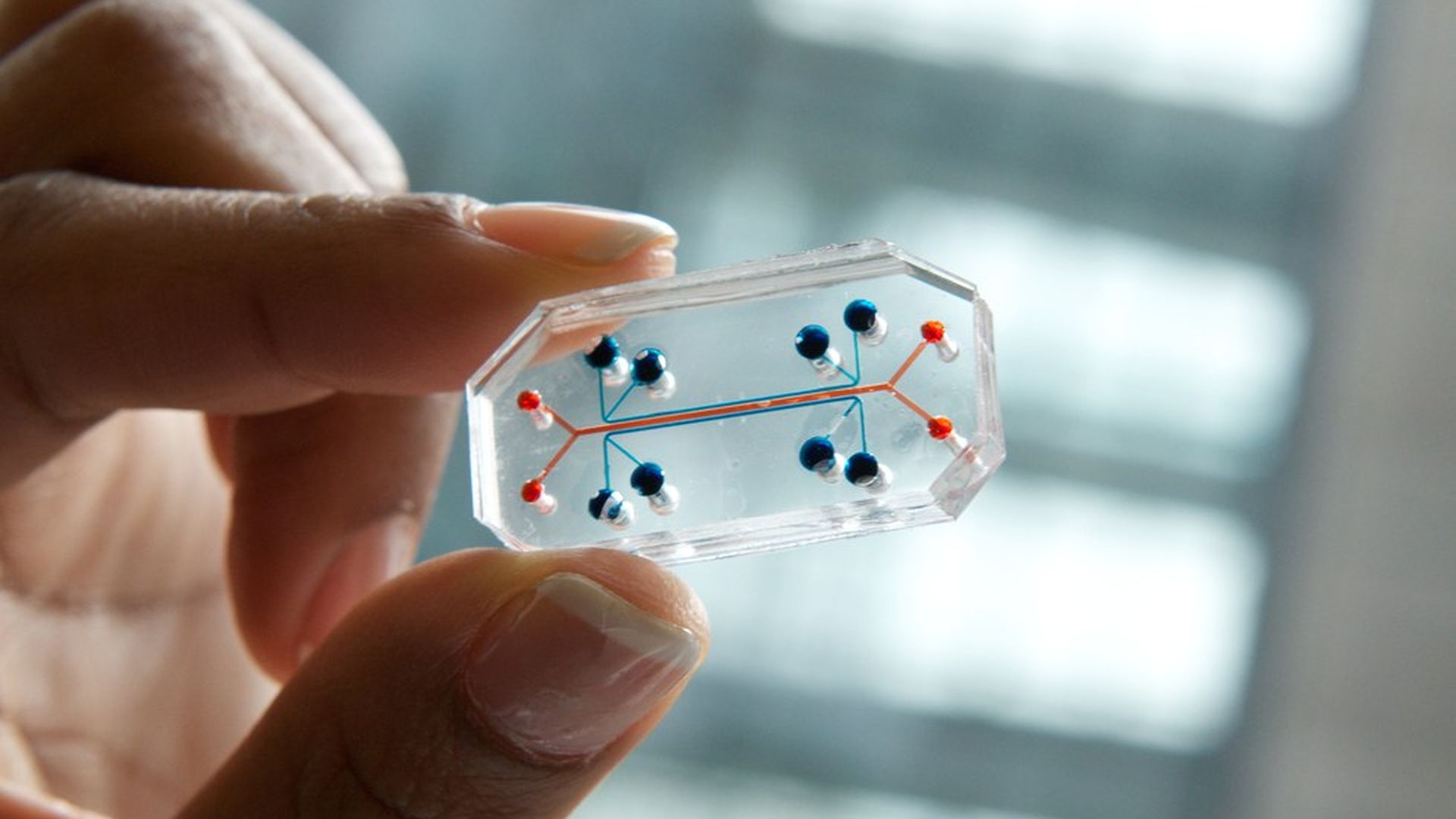

A lung on a chip developed by Harvard University Wyss Institute on a DARPA grant. Photo: DARPA

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is known for creative, high-tech research projects that often sound like science fiction. Now, a philanthropic heavyweight and a former DARPA program director together are pushing for the federal government's health department to have its own version.

The big questions: How would it fit in the health department that also includes the National Institutes of Health? And how will pharmaceutical and other companies be incentivized to take products to market? The answers — and some clever navigating of the potential tensions — could help determine whether an Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, or HARPA, ever gets off the ground.

The players: Bob Wright, the former CEO of NBC and founder of Autism Speaks, is the main force behind the proposal. He's tapped Geoffrey Ling, a neurologist at Johns Hopkins and the former director of DARPA's Biological Technologies Office, to develop the proposed agency and, Wright hopes, lead it.

DARPA gave us the internet, and both say it is worth seeing what the same model could do for much-needed advances in detecting and treating cancers and other diseases.

How it could work: Ling maintains it would complement the discovery work done at NIH: "I'm not saying that HARPA is a panacea and is going to fill all the need areas but it is an approach I can see filling part of these need areas. In my mind, it is just a different way of doing business. It's an entirely different philosophy."

The details: They advocate setting up a semi-autonomous body directly under the Department of Health and Human Services — but independent from NIH.

- HARPA, like DARPA, would be "performance-based, milestone-driven, timeline-driven with the efforts determined by the government," Ling says.

- It would center on contracts between the agency and researchers spanning academia, corporate and government agencies.

Harvard's David Walt, who is not involved in the proposal and was a chair of a now-defunct advisory council of DARPA, says if an ARPA health program is set up correctly and follows the DARPA model closely, it could benefit the health arena. But he points out that health care is a highly regulated environment. "I'd be excited about the prospect of bringing a DARPA-like approach to critical problems in health care but it isn't the same as implementing a new device in the military."

What NIH is doing: Taking science from the "bench to bedside" is within the NIH purview — director Francis Collins set up an institute to do just that. And, right now, the NIH can bypass the grant process and distribute funds through a DARPA-like arm called the Common Fund. Their 2017 budget is about $675 million.

About two-thirds of the work within that fund is toward goals set by the NIH with investigators coming up with ways to attempt to reach them, says Betsy Wilder, who directs the Office of Strategic Coordination at the NIH. DARPA also funds biotechnology projects and collaborates with NIH.

The ask: Wright and Ling want two separate chains of command under HHS and two separate budgets within the department.

- Ling estimates the agency would require a budget of $2 to 3 billion — the equivalent of about 10% of the NIH's $34 billion for this year.

- "We'll be the little sister to the NIH. No problem. But because of the different philosophy and because of the different approach, it needs to go up a separate chain of command. That is absolutely crucial because otherwise it's going to be viewed as competitive and that just isn't right. It's synergistic," Ling says.

- The $6.3 billion 21st Century Cures Act authorized by Congress last year could help to launch HARPA, Wright says. Right now, $4.8 billion is slated to go to the NIH and $1 billion to states for opioid treatment and prevention.

- Wright says, HARPA's success would depend on its ability to use NCI databases and other government assets.

Where it stands: "We've gone to the White House, we've gone to Congress, we've got bipartisan support," Wright says.

Ultimately, it would require congressional authorization — but they're asking the White House to launch it, potentially on a pilot basis. President Trump's budget proposed cutting money for the NIH, and there is a general trend toward consolidating across the federal government, raising questions about where funding for a new program would come from.

What we don't know: Where this will go. A spokesperson for the White House said there was no comment at this point.