Sex-trafficking bill hits a nerve in Silicon Valley

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

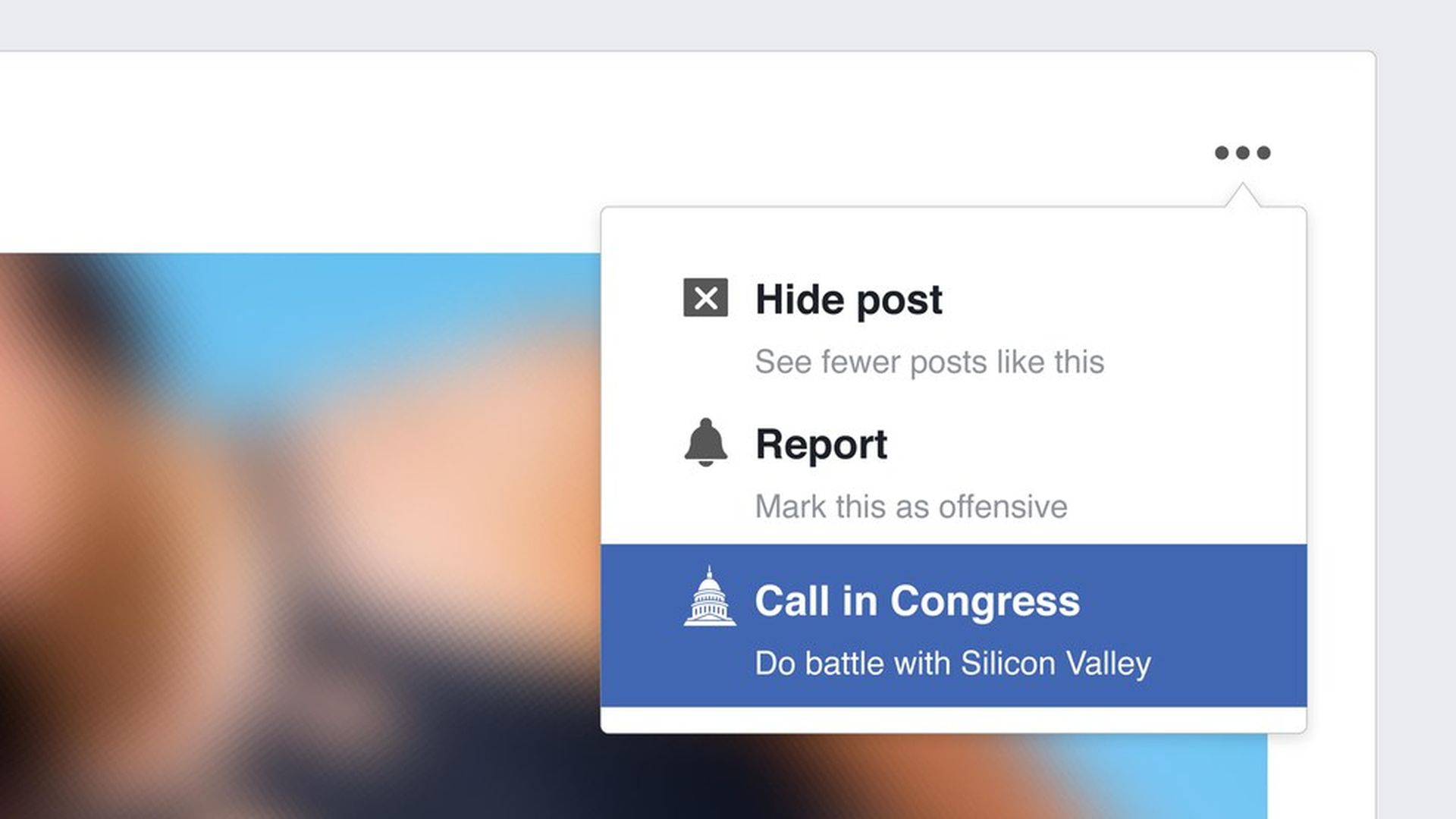

Lazaro Gamio / Axios

Of all the policy fights big internet companies are facing this fall, a sex-trafficking bill with bi-partisan support on the Senate has them rattled the most. And it has the potential to escalate quickly as critics of Silicon Valley firms look for opportunities to hit them where it hurts.

What it does: The bill, backed by senators Rob Portman and Richard Blumenthal, aims to hold online platforms liable for illegal ads that led to sex-trafficking.

Why it matters: Internet companies including Google, Facebook and Amazon say that the bill threatens the core of their business models — because they couldn't have grown to their current size if they were responsible for all of the content they host. But by opposing the measure, they're being painted as not doing enough to help the victims of sex-trafficking.

The details: A provision (section 230) of the Communications Decency Act broadly shields web platforms from legal liability for what their users post or for filtering offensive content. This protects YouTube, for example, from being held legally responsible for all the user-generated content posted by more than 1 billion users. A bipartisan coalition of senators wants to amend that law so that victims of sex trafficking can sue websites that are found in court to have helped facilitate the crime. There's an even harsher bill in the House.

The backstory: Portman and others have been investigating Backpage.com for its connection to sex-trafficking for years, and cited the website for contempt of Congress last year. But lawmakers say that victims will still struggle to find justice if they can't sue the website for its role in trafficking.

- Courts have repeatedly looked at the issue. In August, a judge dismissed pimping charges against Backpage.com, the site that triggered the bill, saying that that Section 230 would continue to shield sites from from being held responsible for allegedly helping traffickers unless Congress changes the law.

Internet companies' reaction: While the companies themselves have stayed quiet, their trade associations and the think tanks they fund have come out swinging against the bill.

- The Internet Association, which represents Google, Facebook, Amazon and others, warned the bill would expose its members to lawsuits and said that it "jeopardizes bedrock principles of a free and open internet, with serious economic and speech implications well beyond its intended scope." Noah Theran, an association spokesman, said in a later statement that the "internet industry has and continues to be committed to finding additional ways to combat trafficking and hold criminal actors accountable."

- The group said in a policy paper that a renegotiated version of the North American Free Trade Agreement should "prohibit governments from making online services liable for third-party content."

- The industry has also suggested that the bill could cause them to pull back on their current efforts to combat content related to sex-trafficking because being aware of the activity at all could expose them to new liability.

The other side: Supporters of the legislation are frustrated with the industry's unwillingness to find a solution to the problem.

- Supporters say the bill sets a high bar for liability and is narrowly tailored to address only the kind of trafficking activity it's meant to target, including allowing companies to continue to filter offensive and illegal content.

- The sponsors were in contact with the industry for more than a year before they announced the bill. Kevin Smith, a spokesman for Sen. Portman, says the companies declined to give "constructive feedback" on the bill.

- This week, lawmakers got a victory in their effort to get other tech backing for the bill: an Oracle policy exec said in a letter that the company supported the bill and that the "legislation does not, as suggested by the bill's opponents, usher the end of the Internet." That'll let Portman and others claim some Silicon Valley support and also gives Oracle another chance to stick it to Google in their long-running fight.

The politics here are complicated. In past policy fights, the tech industry gained the upper hand by rallying users to deluge lawmakers with emails, calls and messages on online platforms, as was seen in the successful effort to crush the SOPA/PIPA copyright bills in 2012.

But sex-trafficking rings endangering children are a much more emotionally charged issue than copyright law. Google and Facebook don't want to be seen as rhetorically linked to sex-trafficking schemes but also worry it opens the door to more legal liability for content on their sites down the road. Lawmakers and children's advocates, meanwhile, argue that these extremely profitable companies have a responsibility and ample resources to help combat sex-trafficking.

Next steps: Senate sponsors could try to attach their bill to a larger piece of legislation (though that can be hard) or move it through committee. There's a similar bill in the House backed by more than 100 lawmakers — but so far most of the focus has been on the Senate.