Axios Capital

September 16, 2018

Welcome to Axios Edge! I'm your host, Felix Salmon, and this here newsletter is going to come out every Sunday afternoon, setting you up for the week ahead. I'm writing it for you, dear reader, so if there's anything you'd like to see, just hit reply and tell me. I read all emails.

- This weekend marks the 10th anniversary of the most intense and memorable moment in the financial crisis, the death of Lehman Brothers. But all's fine now! We're at full employment! The stock market is at record highs! The Fed has a firm hand on the tiller! Nothing could possibly go wrong! So sit back, pour yourself a glass of rosé, and watch some Netflix. Now is the time for complacency.

1 big thing: Debt has stopped growing...

It's not exactly the deleveraging that many hoped for; total debt in mature economies is still near 400% of GDP, a decade after the crisis. But by the same token, after a decade of stimulus bills and bailouts and automatic stabilizers and soaring student loans and ultra-cheap funding costs, it's an achievement in itself that debt hasn't gone up.

- The debt is safer now, too. Governments account for more of it, while the financial-services sector has deleveraged more than anybody else. When governments run into debt trouble, they implement financial repression, which is less painful than crisis-triggering defaults.

...and U.S. households have deleveraged...

...but some of the riskiest debt has grown a lot

At the height of the crisis, there was a terrifying $600 billion in leveraged loans outstanding. This junk-rated debt looked highly likely to default, because it couldn't be refinanced: Just $77 billion of such loans were issued in 2009.

- Here, the deleveraging never really happened, and now we're seeing record issuance (an annualized $666 billion, year-to-date) and record debt levels, too ($1.1 trillion, at last count).

Most of this debt lives in CLOs (collateralized loan obligations), where it doesn't pose a huge systemic risk. It would be much more dangerous if it was being held on banks' balance sheets. But there could be hundreds of billions of dollars in losses if a stock-market correction causes the leveraged-loan window to close.

- The big picture: To put these numbers in perspective, total subprime mortgage originations peaked in 2006 at just over $600 billion.

2. What Lehman wrought

Illustration: Lazaro Gamio/Axios

No one saw the ZIRP* boom coming. When Lehman Brothers was allowed to go bankrupt, it was clear that the crisis was entering a new and much more dangerous phase and there would be a lot of financial carnage.

- But bears didn't make the really big money. Bulls did. Central banks slashed the cost of capital to zero and kept it there for the best part of a decade, encouraging capital-intensive investment. Austere governments demurred, but the private sector made trillions of dollars.

One sector outperformed everything else: companies with slim or negative cashflows, which need extended investment on their way to multibillion-dollar valuations. Some of the biggest examples:

- Tesla raised $19 billion and has an enterprise value of $67 billion.

- Uber raised $22 billion on its way to a $72 billion valuation.

- Ultra-luxury residential construction boomed around the world.

- The entire fracking industry was built on cheap capital. As Amir Azar of TD Securities wrote in a 2017 report:

The real catalyst of the shale revolution was ... the 2008 financial crisis and the era of unprecedentedly low interest rates it ushered in.

The bottom line: We may never again see rates this low for this long — and frankly, we should have reaped greater benefits. Still, many thanks to WeWork (funding: $9 billion, valuation: $35 billion) for the delicious coffee at Axios NYC!

*(Zirp = zero interest rate policy, for non-econowonks).

3. How Lehman went to zero

Crises are nearly always unexpected. When Russia defaulted in 1998, it caused a crisis because the markets didn't see it coming. But Argentina's much larger default in 2001, or Venezuela's in 2018, caused barely a broader ripple because they were so clearly signposted and expected.

- The chart of the last five years of the Lehman Brothers' share price shows a company going to zero in pretty much the most orderly way you could imagine. It doesn't suddenly plunge at the end; rather, the decline begins in mid-January 2007, a full 20 months before catastrophe strikes. This chart is a chronicle of a bankruptcy foretold.

Between the lines: If the crisis really began on Sept. 15, 2008, it's not because Lehman fell, it's because the Fed wasn't there to catch its fall. When shareholders lose money, that almost never has systemic consequences.

- But Lehman was an integral part of the plumbing of the financial system and had tens of thousands of counterparties around the world. Those counterparties woke up in a world where they had no idea whether they owned their assets anymore. And that is the kind of thing that causes a crisis.

4. By the numbers: Americans are clueless about the stock market

Almost half of Americans think the stock market has failed to rise at all since 2008, according to a new survey from Betterment. The correct answer is the last one in the chart above: The stock market is up by more than 200%.

5. Reality check: Valuations

The "most hated bull market in history" continues to march higher. And because there's very little speculative fever, it can be hard to grok how stratospheric many valuations have become.

Put aside for one minute the crucial question of whether they're justified and just wonder at how far we've come from famously frothy moments in the not-so-distant past:

- December 1996: Alan Greenspan gives his notorious "irrational exuberance" speech. That day the S&P 500 closed at 739; after two stock-market crashes, it's over 2,900 now. The 10-year Treasury yield was 6.24%, versus 2.9% today. Meanwhile, consumer prices have grown by a relatively modest 58%.

- December 1998: CIBC Oppenheimer analyst Henry Blodget puts a dizzying $400 price target on Amazon stock, which was then trading at $243 per share. Blodget's report single-handedly sends Amazon's share price up to $289. Today, those shares are trading at about $12,000 each, if you ignore the stock splits. And Morgan Stanley has a new price target of a split-adjusted $15,000.

- February 2000: The absolute peak of dot-com bubble madness was surely the Pets.com IPO. The company raised $82.5 million by selling shares at $11 each. They rose as far as $14 before crashing to earth a few months later. Its top-tick market capitalization? $369 million. Compare that to the $3.35 billion that PetSmart paid for Chewy.com last year.

6. The tech giants' accountability crisis continues

Mark Zuckerberg controls a majority of the votes on Facebook's board, and he can basically do whatever he likes. Other tech giants, including Google, also have dual-class share structures. But even companies with single-class share structures are accountable only to their shareholders, which makes a lot of other stakeholders unhappy.

A short list of people who are on the warpath against the tech giants would include:

- Donald Trump (of course)

- Bernie Sanders

- EU competition commissioner Margrethe Vestager

- The archbishop of Canterbury

- The Senate Intelligence Committee

- The UK parliament

- Google's employees

- Facebook's employees

The biggest existential threat to the tech giants now is public mistrust, much more than any potential EU fine. Regaining that trust has to be their top priority.

- What's next: Get out in front of the criticism. Embrace corporate citizenship. Respect politicians as the duly elected representatives of the companies' users. Put worker representatives on the board, and user representatives, too. Implement meaningful accountability.

7. What to watch: Crashing currencies

Currencies in developing countries have fallen off a cliff, Axios' Courtenay Brown writes. The Argentine peso has lost more than 50% of its value against the U.S. dollar this year, and the Turkish lira is doing almost as poorly.

- What's going on: Argentina and Turkey are both suffering from fiscal crises that have hammered their currencies. Go deeper.

8. Congratulate Joe and Guru on their new jobs!

Joe Ianniello is the new acting CEO of CBS, while Guru Gowrappan is taking over at Oath. In both cases, a strategy-and-operations guy is replacing a sales guy, in much the same way as a banker might take over from a trader at Goldman Sachs.

- Les Moonves and Tim Armstrong both rose up the ranks by selling highly coveted ad space to massive brands. They're probably the last of that breed, however.

- The new emperors of advertising are robots, not men, and the main skillset of a media CEO is to be able to marshal the largest and strongest robot armies.

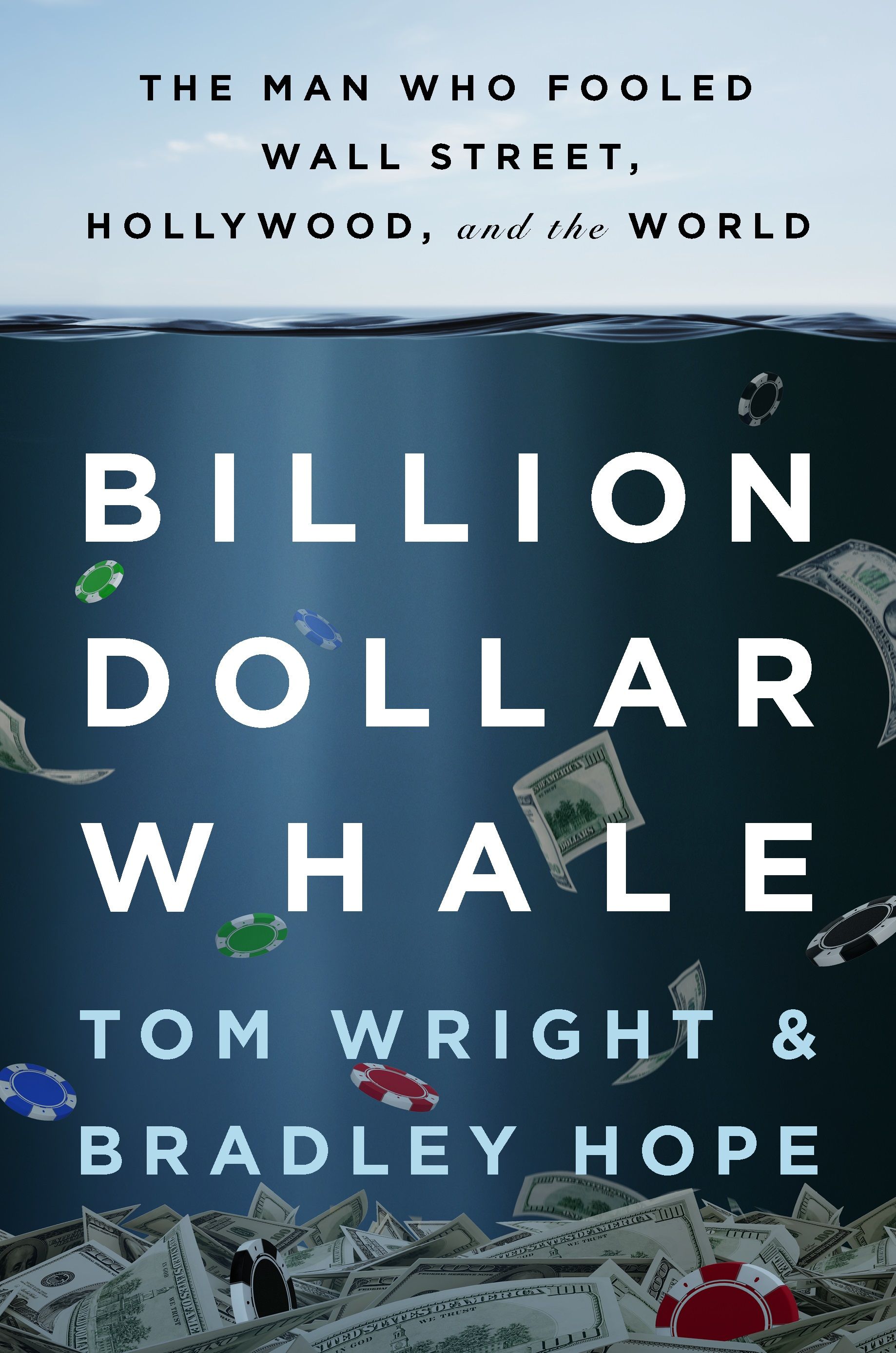

9. This week: The heist of the century

Tuesday is the publication date of Billion Dollar Whale, the most jaw-dropping tale of this year‘s Summer of Scam. If you liked Bad Blood or Jessica Pressler's Anna Delvey story, of if you just want to learn how easy it is to persuade international financial institutions to help you steal billions of dollars, then you're going to love this book.

- It’s the inside story of Jho Low, who created Malaysia’s multibillion-dollar 1MDB development bank as a private slush fund for himself, his friends and important political patrons.

- The book opens with a multimillion-dollar Las Vegas party featuring Alicia Keys, Leonardo DiCaprio, Benicio Del Toro, Britney Spears, Kanye West, Martin Scorsese, Robert De Niro and many others — it just gets crazier from there. (The Wall Street Journal yesterday ran a book excerpt about the epic party.)

The book party is tomorrow in New York. Don't expect Mr. Low to be there.

Bonus: Tweet of the week

10. Building of the week

Brutalism is named after béton brut, the French name for the unadorned architectural concrete that all brutalist buildings are made of. At the National Theatre in London, Denys Lasdun embraced the grain of the wooden forms he used to cast the concrete.

I'd like to make this a weekly feature, so send me pictures of your favorite buildings! (So long as they're in the public domain or you own the usage rights, of course.)

Sign up for Axios Capital

Learn about all the ways that money drives the world