Axios Codebook

January 22, 2019

I haven't seen the nominations yet. But with hard work and a little prayer, we're confident this is the year Codebook is finally up for an Oscar.

1 big thing: A startup-style fix for tech-policy gap

A woman checks her cell phone as she waits in line to enter the U.S. Supreme Court. Photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images

Tech policy debates often end up slanted toward the industry's perspective because lawmakers use companies as the experts, and historically, recruiting experienced technologists into policymaking has been tough.

The Aspen Institute is aiming to shift that imbalance with a new program at its Tech Policy Hub, which is now taking applications for its first fellowships.

Why it matters: There is a literal and figurative country between Silicon Valley and Washington, D.C. And it's hard to solve a technology problem where lobbyists are the only tech-adept people in the conversation.

The Aspen program is loosely based on startup incubators — the boot-camp-type programs meant to mold fledgling companies into something presentable to a venture capitalist.

- In this version, policy experts will help technologists evolve a single idea into a single demonstrable prototype worthy of presenting to a lawmaker or other influencers. That could be anything from model legislation to a technological fix for a policy issue.

- "Traditionally, a think tank would write a white paper to 'tell' a solution," said program director Betsy Cooper. "We’re looking for 'show.'"

- A key benefit of startup incubators is that their reputations get venture capitalists to hear a pitch. The well-established Aspen Institute may have the juice to pull off the legislative equivalent.

The Tech Hub comes at a unique moment for Silicon Valley, where the first response to social problems has always been through circuitry and software.

- In recent years, many have realized that problems like privacy, encryption or threats to democracy can't or won't be solved outside of Washington, D.C.

- "There’s been a sea change away from the old Silicon Valley idea that D.C. just gets in our way," said Cooper.

There aren't many techies in Congress. Forget the lawmakers — there aren't many tech-trained aides. By the count of Travis Moore, director of TechCongress, a group helping match lawmakers with tech staffers, only 9 of the thousands of Congressional staffers came from tech backgrounds.

- Moore, who was previously legislative director for Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.), notes that when Congress wrote the Affordable Care Act, the House Committee on Energy and Commerce had 3 doctors on hand.

- Contrast that with his experience with a threat information sharing bill from around the same time. "I was trying to understand data sharing and could find no one in Congress. I had to get briefed by a corporation. And that means I received corporate spin," he said.

- That's a sentiment shared across Washington. "In general, ever since Newt Gingrich killed the Office of Technology Assessment, the Congress has had to rely on lobbyists and their paid consultants for tech insights," noted Tom Wheeler, former chair of the FCC and current visiting fellow at the Brookings Institute.

What's next: If the incubator idea works for tech policy, Aspen's Cooper says she hopes to bring the same framework to other issues.

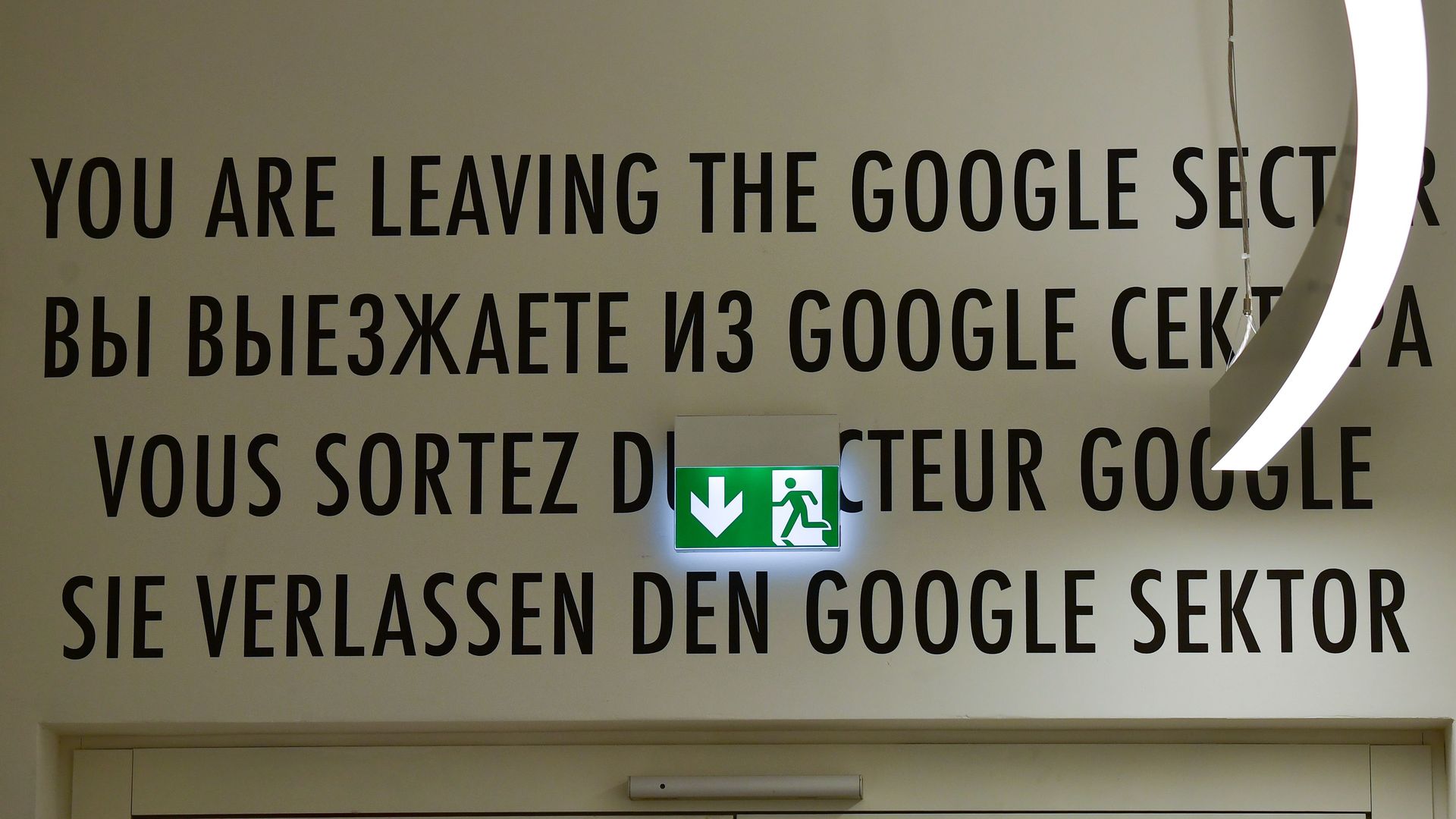

2. Google's busy weekend in Europe

A sign indicating the borders of the sectors in allied occupied Germany after WWII is pictured during the opening day of Google's new Berlin office, Jan. 22. Photo: Tobias Schwarz/AFP/Getty Images.

- France struck Google with the first major fines for a U.S. company under Europe's sweeping data privacy law, the General Data Protection Regulation. The French data regulator said the fines stem from Google not being transparent enough about data collection practices for advertisements.

- Google lost a major case over the "right to be forgotten," the EU's rule allowing some citizens to make search engines remove links to content concerning them. In this case, a Dutch surgeon censured by the medical board had the right to delist a link to a site containing accurate information about that doctor's actions, as the site would serve as a blacklist. Here's The Guardian's summary.

- Google is considering ending its Google News service in Europe as the continent mulls a copyright law forcing internet platforms to pay publishers for even small excerpts of articles that are rebroadcast, reports Bloomberg.

3. WhatsApp targets fake news by limiting message forwarding

Facebook's secure messaging app WhatsApp announced Monday that it would cap the number of people a user could forward a message to at 5 in an attempt to prevent false stories from spreading too quickly.

What they're saying: “We’re imposing a limit of five messages all over the world as of today,” Victoria Grand, WhatsApp vice president for policy and communications, told Reuters, announcing the change in Indonesia.

Why it matters: U.S. WhatsApp users are probably most familiar with false allegations inflaming the political climate. That's bad, but nothing near as bad as what's happened in India, where rumors have lead to lynchings.

Because WhatsApp is encrypted in a way that not even Facebook can read the messages — thus preventing oppressive regimes from subpoenaing Facebook for the messages — there aren't many good options to moderate links and other content from propagandists or well-meaning-but-incorrect uncles.

4. Malware mined much of Monero

4.32% of the Monero cryptocurrency was mined by malware infecting victim's systems, according to researchers at the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid and King's College London. The study was published earlier this month (I came across it on ZDNet).

By contrast, the United States began rolling out security enhancements to $10 and $20 notes when 1 in 10,000 bills were counterfeit — the paper-currency equivalent of being mined by criminals.

That's not a perfect analog. Obviously, the illicit U.S. bills were not real, while Monero is actual cryptocurrency being created through illicit means — sort of illegitimate legitimate currency.

5. Odds and ends

- A must read in the New Yorker about how voting machine lobbyists shape elections. (The New Yorker)

- Finally an online quiz worth taking: See if you can tell which emails are phishing attempts and which ones aren't. (Google and Jigsaw)

- It's hard to know whether all of 4,000 listed Latvians really informed for the KGB. (New York Times)

- The NSA at ShmooCon: "You know you want to try it." (Twitter)

- A data exposure at an online casino group, just in time for the Super Bowl. (ZDNet)

We'll see you on Thursday!

Sign up for Axios Codebook

Decode key cybersecurity news and insights. With Sam Sabin.