Axios Capital

February 25, 2021

Situational awareness: President Biden has officially revoked his predecessor's executive order "Promoting Beautiful Federal Civic Architecture." Fans of interesting federal architecture are breathing a bit more easily this morning.

- In this week's newsletter, I dive into the world of NFTs and SPACs, and wonder what on earth is going wrong with our payments infrastructure. It's 1,737 words, a 7-minute read.

1 big thing: The NFT frenzy

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

Move over, GameStop. The newest speculative game in town is NFTs — digital files that can be owned and traded on a plethora of new online platforms.

Why it matters: Most NFTs include some kind of still or moving image, which makes them similar to many physical art objects. Some of them, including a gif of Nyan Cat flying through the sky with a Pop-Tart body and rainbow trail, can be worth more than your house.

- How it works: Most crypto assets are like dollars, or stocks: They're fungible, which means that one bitcoin, or share of IBM, is worth exactly the same as any other bitcoin, or share of IBM. NFTs, by contrast, are non-fungible tokens: They're unique objects that live on a blockchain and are valued as collectors' items.

By the numbers: Nyan Cat sold for 300 ETH (the ethereum cryptocurrency), or about $580,000 at the time the bid was entered on Feb. 19. An artist going by the moniker "Beeple" just saw one piece change hands for $6.6 million, and has consigned a major digital work to auction house Christie's in an online auction that will end on March 11.

- One fake Banksy, by an artist calling themselves Pest Supply, sold for more than 60 ETH, or about $100,000. The artwork featured a stencil saying, "I can't believe you morons actually buy this NFT shit." It's not clear where or how the buyer could resell the work, given that the Opensea platform has now disabled all future sales by that artist.

- A short clip of a LeBron James dunk from 2019 sold for $208,000, on a day when more than 20,000 buyers spent more than $45 million in total buying NBA TopShot clips. European soccer is also getting in on the game.

The catch: Most NFTs (but not TopShots) live on the ethereum blockchain, which has a massive carbon footprint. Artist Joanie Lemercier calculated that one release of his art on NiftyGateway was responsible for more carbon emissions than his entire physical studio emitted in 18 months.

The big picture: Our digital lives are surrounded by countless digital objects. NFTs are a way to imbue such objects with financial value. When that happens they take on a new level of significance and importance.

- They also become vehicles for speculation, whose financial value is generally entirely unrelated to their artistic value.

2. Why it's happening now

Illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios

NFTs are at least seven years old.

- Flashback: At a TechCrunch conference in May 2014, technologist Anil Dash and artist Kevin McCoy talked about such tokens as a way to bring together "people who are literate about Bitcoin, cryptography, and block chain" with "people who care about humanity, emotion, expression, art & culture."

The big picture: That was a noble dream, and also a doomed one.

- NFTs really took off after blockchain technology became commoditized, and also after the objects themselves lost most of their humanity, emotion, expression, art and culture. If you look at hashmasks or CryptoPunks or much of the rest of the NFT world, there's no connoisseurship at play — no correlation between artistic merit and financial value.

How it works: NFTs have become an institutionalized popularity contest, in an irony-drenched Extremely Online world where popularity can come from popular culture — or just from being on the right website at the right time.

Between the lines: The real driver of the NFT phenomenon lies in the combination of three things.

- Excess wealth and liquidity, especially in a world where a lot of people are experiencing windfall cryptocurrency profits.

- Zero interest rates and soaring technology stocks. Items without cashflows (gold, bitcoin, wine, cars, trading cards, sneakers, handbags, etc) are just as attractive as zer0-dividend stocks like Amazon or Tesla, which in turn are more attractive than conventional bonds or dividend-paying stocks.

- Gamification, speculation, and the FOMO idea that if you get in to a hot thing early, you can make enormous profits.

The bottom line: Established artists can easily get any kind of certificate of authenticity they need from their galleries. The artists turning to NFTs are generally outsiders who don't make the kind of art that traditional collectors like, but who know how to tap into a large online following.

3. Payments failures

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

Modern capitalism runs on a smooth global electronic payments system that works in an efficient and predictable manner. That system is beginning to show cracks.

Driving the news: The majority of the U.S. payments infrastructure came to a shuddering halt on Wednesday when a "Federal Reserve operational error" caused a whole slew of services to stop working.

- ACH went down, which covers most transfers in and out of bank accounts, along with Check21, which covers checks; FedCash; and more.

- Fedwire — the self-described "premier electronic funds-transfer service that banks, businesses and government agencies rely on for mission-critical, same-day transactions" — also went down.

Between the lines: The Fed is unlikely to give much public explanation of what went wrong. CNBC's David Faber, however, reported that the Fed did try turning the system off and on again — and that didn't work.

Flashback: One layer up from the public payments infrastructure are private payments protocols, which are also brittle and prone to error.

- Last August, Citibank accidentally wired $894 million to a group of Revlon creditors. Adding insult to injury, a judge ruled this month that the creditors who didn't voluntarily return the money were allowed to keep it.

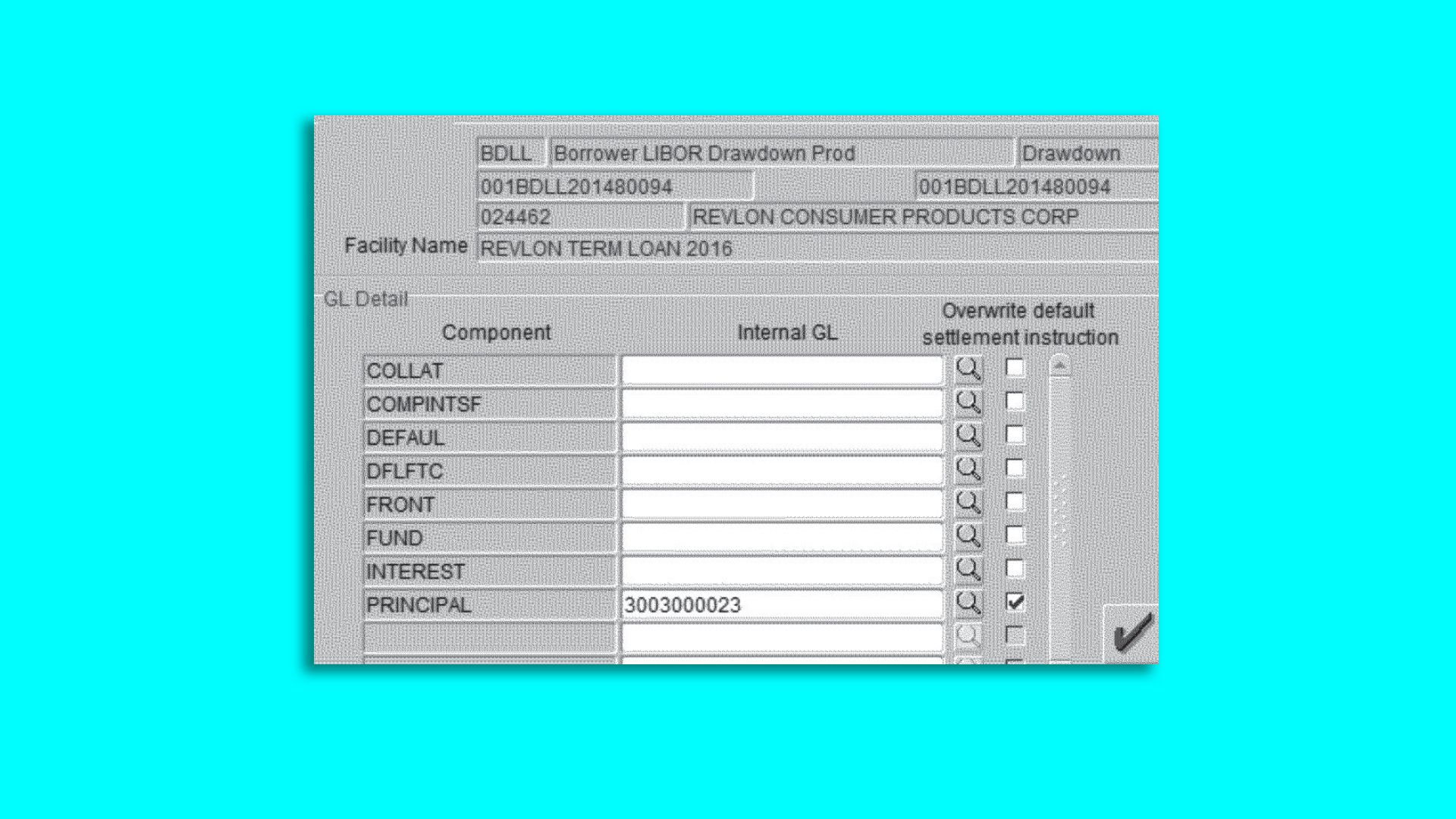

The judge's ruling sheds a lot of light on just how old and creaky Citibank's Flexcube payments infrastructure is.

- The software is incapable of sending principal and interest payments to just one creditor, as was intended in this case. Instead, it needs to be programmed to send principal and interest payments to all creditors, but with most of that principal diverted to an internal "wash account."

- The diversion to the internal account requires three different boxes to be ticked on this screen.

In reality, while the "principal" overwrite box was ticked, the "fund" and "front" boxes were not, which meant that the principal ended up leaving the bank.

The big picture: While the Federal Reserve has chided Citibank for its inadequate internal controls, no one has similar oversight over the Fed.

The bottom line: There's something wrong with America's payments infrastructure, which is still years away from the kind of real-time payments that are commonplace in countries from Sweden to India.

- Cryptocurrency is not the solution, however. As the Citibank and Fed stories demonstrate, mistakes will always happen. That means there has to be some kind of way to reverse transactions — something that remains impossible by design with most cryptocurrencies.

4. Confusing SPACs, Lucid edition

Illustration: Annelise Capossela/Axios

You've never seen a Lucid automobile, let alone driven one. Still, at the close of trade on Wednesday, Lucid Motors was valued by the stock market at $46 billion — roughly the same as Ford Motor.

Why it matters: In the absence of any actual product, the main driver of the electric vehicle start-up's reputation has become the stock market. Which means, in this case, a SPAC. The result has been much confusion.

How it works: The company taking Lucid public is a special-purpose acquisition company, or SPAC, with the unwieldy name of Churchill Capital IV. For the time being, CCIV, as it's known to traders, is simply a box of money holding $2.1 billion in cash.

- CCIV has agreed to swap that cash for 258 million shares in Lucid, as part of a bigger deal that also includes outside investors putting in another $2.5 billion for 167 million shares. In return, Lucid gets not only $4.6 billion in cash but also a stock-market listing.

- The deal is fantastic for CCIV. It has turned its $2.1 billion into shares that, at Wednesday's close, are worth more than $7 billion.

Driving the news: After the deal was announced, headlines started appearing saying things like "High-profile SPAC craters" or "Lucid Motors confirms SPAC deal: CCIV stock down 25%." Those headlines risked giving the impression that the stock market didn't welcome the deal, or that the valuation of Lucid had somehow fallen.

- Reality check: The stock market is still giving this deal two thumbs up. It loves Lucid, which now carries a truly stratospheric valuation far greater than either CCIV or Lucid was valued at pre-merger.

The bottom line: One of the biggest problems with SPACs is that most normal stock-market investors don't yet fully understand how they work.

5. The gyrations of CCIV

At the beginning of this year, CCIV was valued at $10 per share, like most other SPACs — just the value of the cash it held.

- When rumors started circulating that CCIV was going to become Lucid Motors, the stock began to rise.

- At modest levels in the $10 to $15 range, that trade made a certain amount of sense.

- The logic: CCIV was probably going to get private equity companies to invest fresh money into Lucid, and private equity companies' valuation algorithms are generally more conservative than the stock market as a whole, when it comes to electric vehicles. So if PE was going to buy in at $10 per share, maybe it made sense to front-run the merger by buying CCIV at say $15 per share.

Things got out of hand, however, with CCIV stock trading at more than $60 per share before the valuation of the merger deal was announced. That price had no implied valuation for Lucid; it was simply a momentum trade that a stock that was rising sharply would continue to rise.

Once the valuation was announced, the stock fell to a magnificent level for Lucid shareholders but a disappointing level for anybody who had bought CCIV shares at the peak. The momentum trade was over, disgusted traders sold out of their positions, and that selling drove the price of the stock down even further.

The bottom line: Once the merger is finalized and CCIV starts trading under its new ticker symbol of LCID, it will be possible to look to the stock as a reflection of what's going on with the car company. For the time being, however, it's trading mostly on technical factors.

6. GameStop: It's back

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

7. Coming up: Buffett's annual letter

Photo: Ankit Agrawal/Mint via Getty Images

Warren Buffett's annual shareholder letter is out on Saturday, writes Axios' Courtenay Brown, alongside Berkshire Hathaway's fourth-quarter and full-year earnings.

- Look for updates on Berkshire's ramped up buybacks during the pandemic, as well as news on what Buffett thinks about his monster exposure to Apple stock — some $120 billion, as of his latest filing. That's more than 20% of Berkshire Hathaway's total market value.

8. Building of the week: Stanley Mosk Courthouse

Photo: Frazer Harrison/Getty Images

Legendary California architect Paul Williams (1894-1980) is mostly famous for his homes. He designed more than 2,000 of them over more than 50 years, including many for celebrities such as Lucille Ball and Frank Sinatra.

- He was also a master of civic architecture, however, designing hotels, restaurants, churches, hospitals, and also the Los Angeles Superior Court Stanley Mosk Courthouse, built in 1958.

- In 1921, Williams was the first African-American west of the Mississippi to become a registered architect; he then became the first Black member of the American Institute of Architects in 1923.

Sign up for Axios Capital

Learn about all the ways that money drives the world