Study finds surging water volumes needed for fracking boom

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

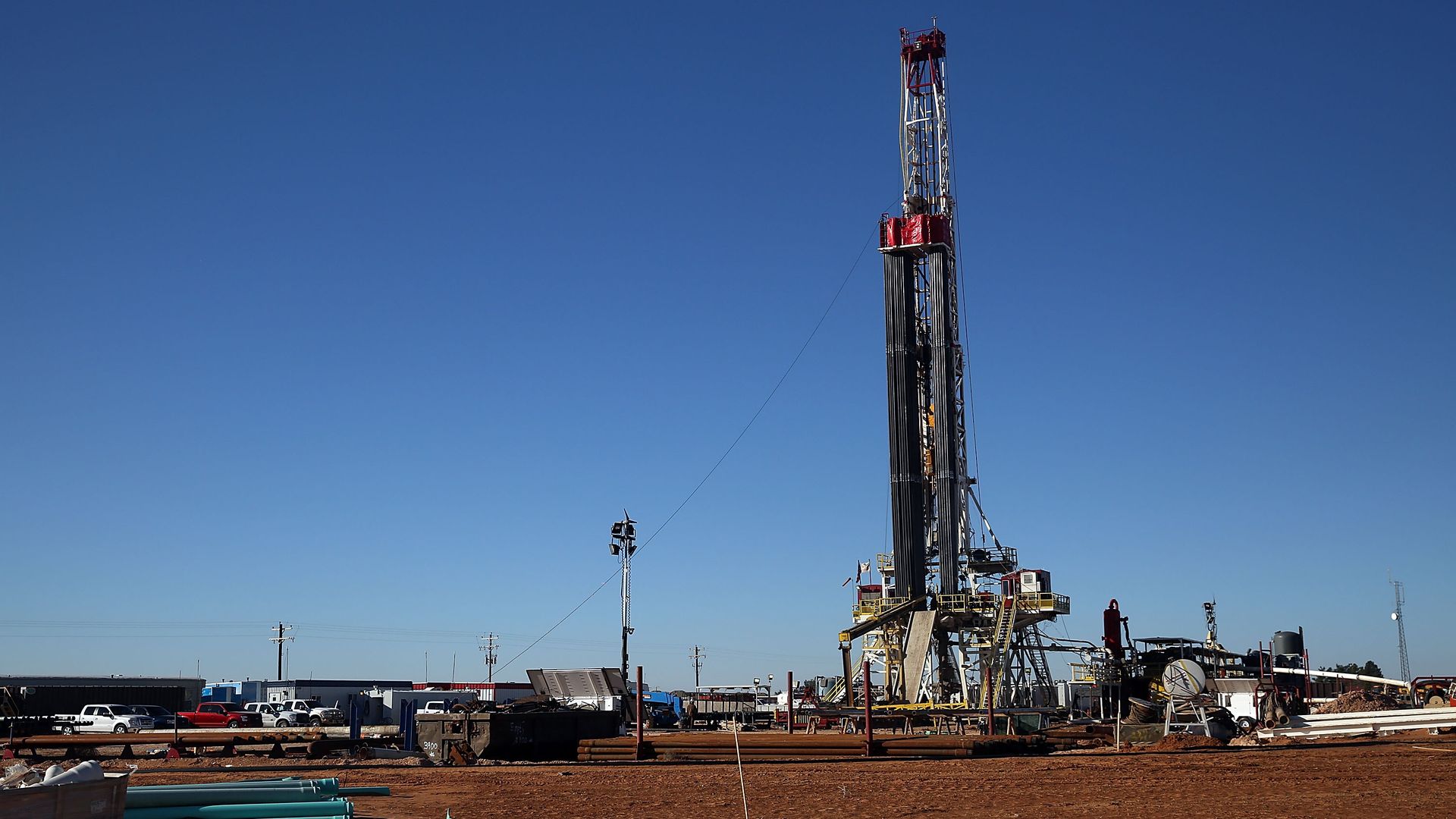

A fracking site in Texas. Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

The amount of water needed for new oil and gas wells developed via fracking has surged in recent years — and it's slated to keep rising — Duke University researchers conclude in a new paper.

Why it matters: It underscores resource challenges, especially in arid regions like West Texas that accompany the decade-old boom in fracking and horizontal drilling, which has pushed U.S. oil and gas production to record levels.

- The study in the peer-reviewed journal Science Advances looks at data for wells developed between 2011 and 2016 in major shale oil and gas regions.

What they're saying: "Previous studies suggested hydraulic fracturing does not use significantly more water than other energy sources, but those findings were based only on aggregated data from the early years of fracking," Duke earth scientist Avner Vengosh said in a statement.

- The extraction technique, which unlocks hydrocarbons trapped in shale rock formations, involves high-pressure injections of water, sand and chemicals.

The details: Water use per well grew by up to 770% as the length of lateral wells has expanded, although the increase varies by region and was most pronounced in the booming Permian Basin of West Texas and New Mexico.

- Volumes of salty groundwater water that comes out of fracked wells — called flowback and produced (FP) water — in the first year of production have grown by up to 1,440%.

- Salts, "toxic elements" and other materials in this flowback water "pose contamination risks to local ecosystems from spills and mismanagement," the paper states.

- Threat level: "The predicted increasing water use and FP water production in the Permian and Eagle Ford basins are alarming given the extreme water scarcity in these regions," the paper warns.

What's next: Looking out to 2030, cumulative volumes of water for developing wells and the amount of FP water could grow by up to 50-fold in gas-producing shale regions and up to 20-fold in shale oil regions — although there are a lot of variables at play.

The bottom line: "As unconventional gas and oil exploration is expanding globally and other countries begin to follow the U.S. shale revolution (for example, China) ... the results of this study should be used as guidance for the expected water footprint of hydraulic fracturing at different stages of energy development," the study concludes.