Corruption anxiety

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

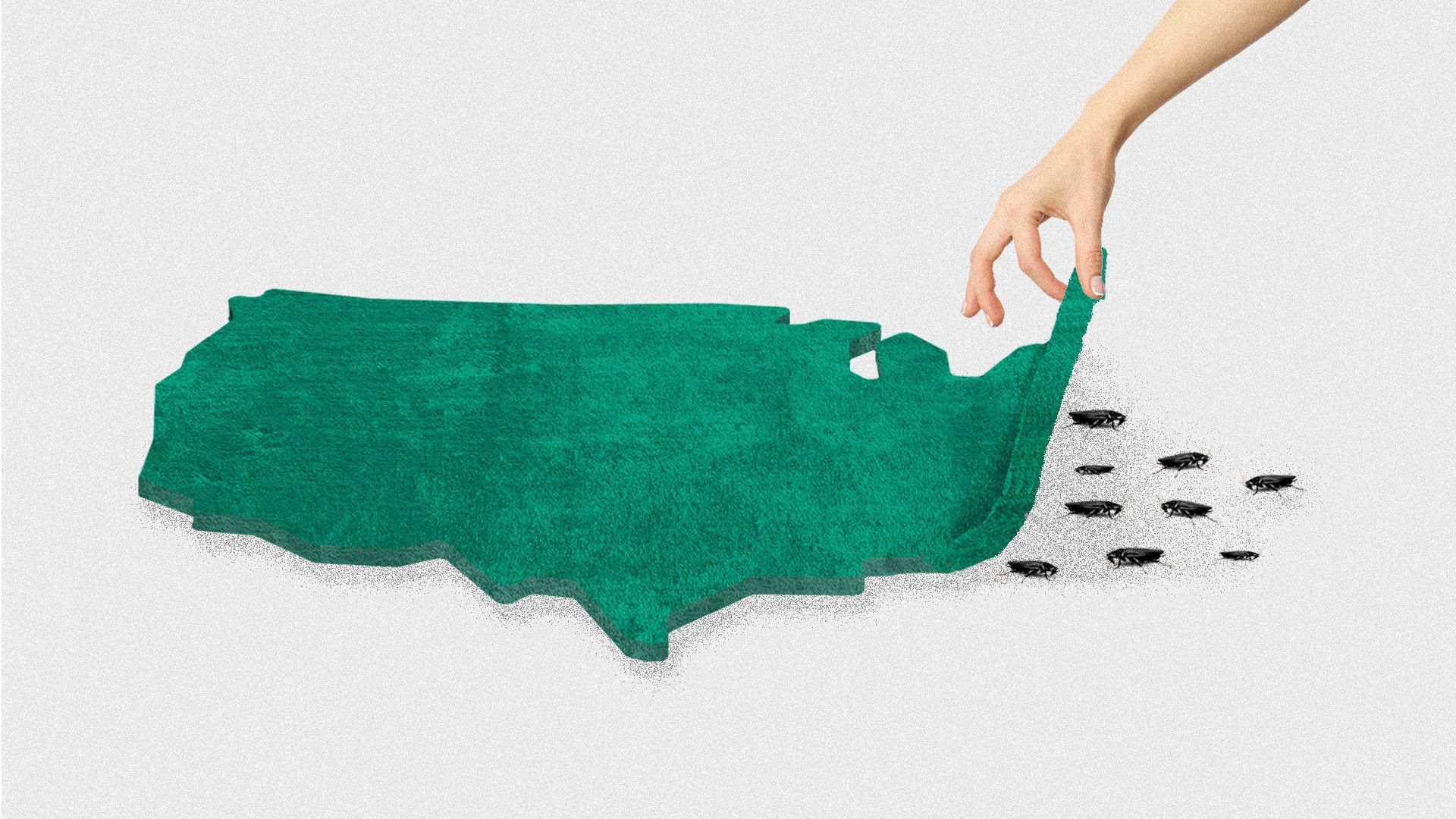

Dayo Olopade, a Nigerian-American journalist and technologist living in London, used the term "corruption anxiety" to describe "the knowledge that society can be and has been manipulated to favor the powerful, at your expense" in a speech at Georgetown University on Tuesday.

Why it matters: It's the sentiment that drove the Arab Spring, but it's not confined to developing countries. The Tea Party, Occupy, the Brexiteers, the Yellow Vests, even Donald "stop this corrupt machine" Trump — all of them feed from a well of broad-based corruption anxiety. As Olopade puts it: "Corruption anxiety unifies the populist left and the populist right."

The big picture: Corruption scandals are magnified by each other. Theranos and Goldman Sachs and Martin Shkreli and Purdue Pharma and the Fyre Festival and the Catholic Church and billionaire Jeffrey Epstein and parking placard abuse and police violence and all the various Trump administration scandals aren't bad apples: They're part of a pattern, one that the American public is hyperaware of. These headlines foment mistrust in the fairness of the entire system.

Be smart: Western countries are generally perceived as less corrupt than most countries in Africa. But perceptions don't always mirror reality. "Our current corruption discourse is a form of geopolitical racial profiling," says Olopade. Any given act of corruption tends to get blamed on an individual actor in the West, while being considered symptomatic of a broader malaise in a place like Nigeria.

- Okwui Enwezor, the great Nigerian art curator, moved to America from Nigeria in the 1980s and found what he described as "a very affluent but unjust society."

- Nordic companies, especially, are more than capable of highly corrupt activity, without Norway or Sweden being considered corrupt countries.

- "Despite the big scandals hitting Siemens or Daimler or Volkswagen," deadpans Olopade, "I never encounter polite grimaces when discussing doing business in Germany."

- Meanwhile, Western nations and institutions are more than happy to play host to African kleptocrats.

The bottom line: The Mueller report has refocused America's attention on malfeasance during the 2016 election campaign. But as Robert Rotberg puts it in his book about corruption, “Greed never stops at the edge of a presidential palace." The more frequently everyday Americans are reminded that our system is rigged, the less they're going to be willing participants in that system.