Jul 5, 2023 - Energy & Climate

UN agency says Japan can release radioactive Fukushima water into sea

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

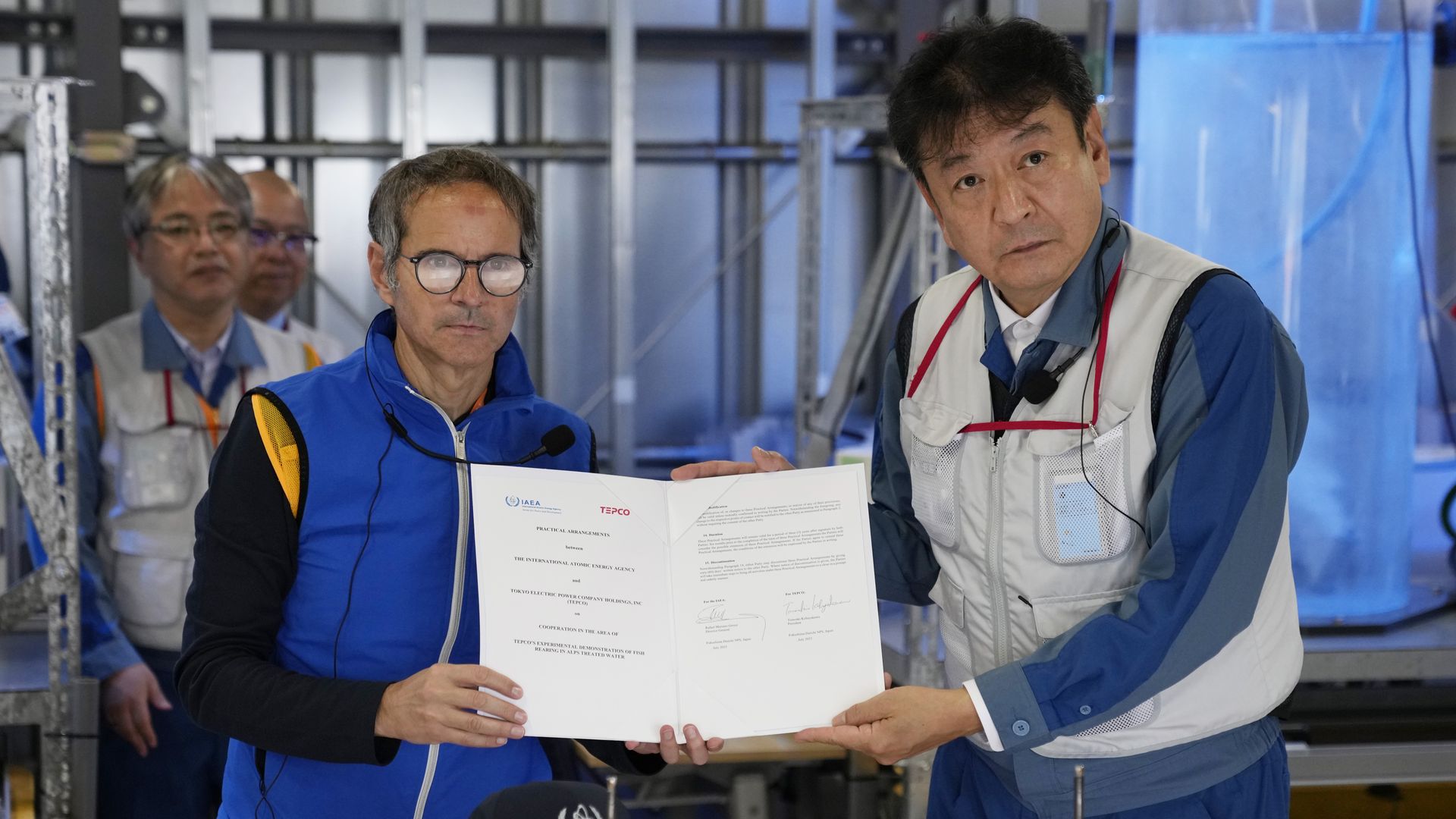

Rafael Mariano Grossi, director general of the IAEA, left, and Tokyo Electric Power Co. President Tomoaki Kobayakawa hold an agreement on July 5 at the damaged Fukushima nuclear power plant. Photo: Hiro Komae - Pool/Getty Images