The long voting rights fight for Florida's ex-felons

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

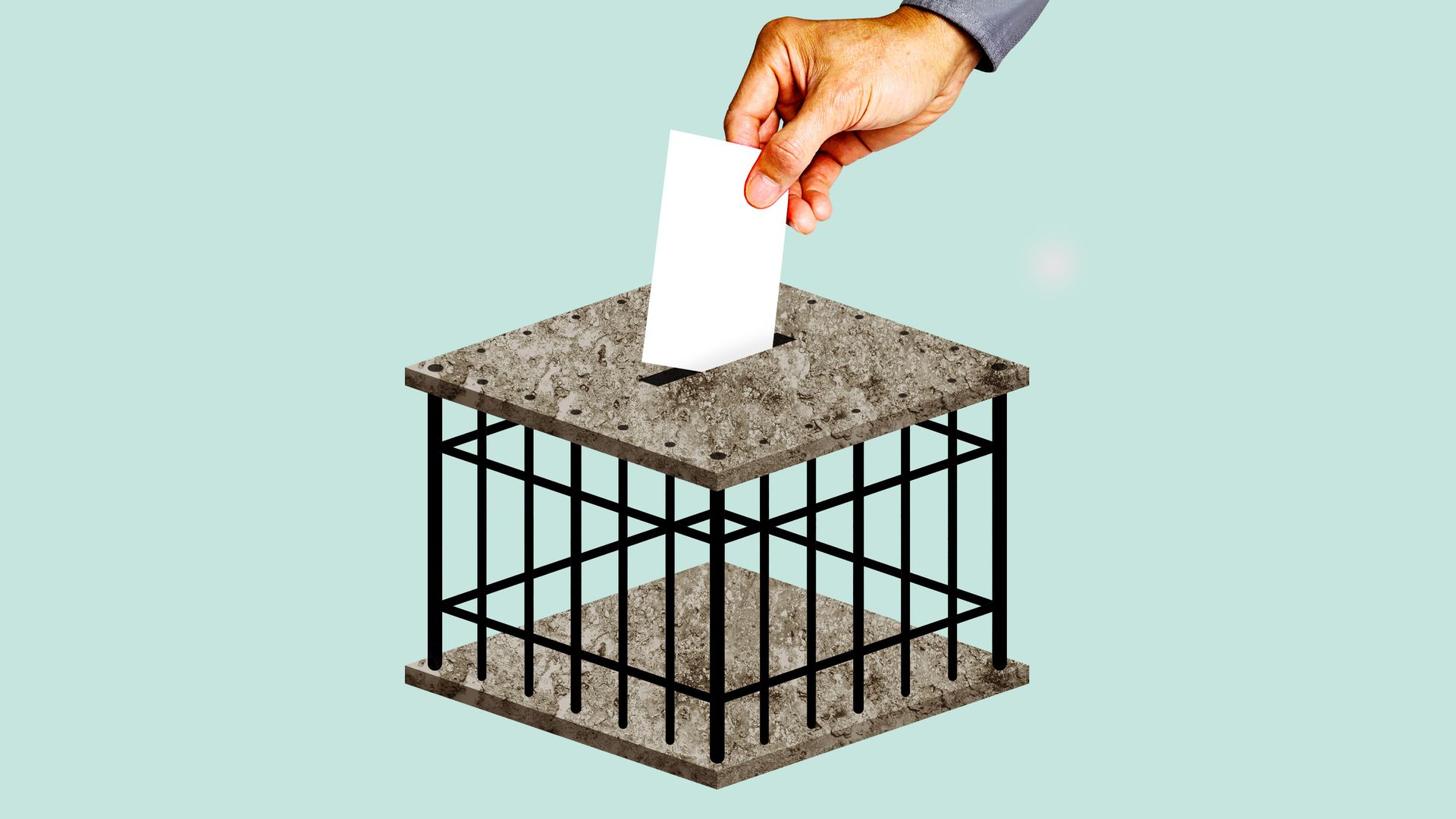

Illustration: Lazaro Gamio / Axios

A federal appeals court handed Florida Gov. Rick Scott a decisive victory this week when it temporarily blocked a federal judge’s ruling that urged the state’s executive clemency board to overhaul its “fatally flawed” process of restoring felons’ voting rights by Thursday.

Why it matters: The order issued late Wednesday, which affects an estimated 1.5 million convicted felons, comes as reform advocates have been fighting to restore their voting rights for nearly two decades.

- People with past felony convictions are permanently barred from voting, and they have to wait up to eight years to request Scott and the clemency board to consider restoring it.

- Felony disenfranchisement laws affect about six million nationally, but Florida, which remains the most stringent, bans more people from voting than any other state.

Timeline:

- September 2000: A federal class-action lawsuit against then-Gov. Jeb Bush, challenged the constitutionality of the ban, which plaintiffs said barred an estimated 600,000 people from voting. They argued that the prohibition dating back to 1868 was used to prevent newly enfranchised blacks from voting during the Reconstruction and Jim Crow era.

- The state denied that argument, and the U.S. Supreme Court had declined to hear the case.

April 2007: Then-Republican Gov. Charlie Crist enacted clemency reforms that automatically restored voting rights to non-violent offenders. The new rules no longer required a hearing or petition, and the clemency board had 30 days to review and grant approvals. Crist (D), a U.S. Rep, wrote in an Orlando Sentinel op-ed last year that voting rights for 155,315 Floridians were restored in four years. An estimated 950,000 were disenfranchised.

March 2011: Scott unraveled the Crist-era clemency rules soon after taking office in 2011. He set a five-year minimum waiting period for nonviolent ex-felons and eight years for others. Those who were denied have to wait at least two years to re-apply.

- Scott has only approved 3,008 applications since 2011, a spokesperson at the state’s Commission on Offender Review told Axios this week. Meanwhile, there's a backlog of more than 10,000 applications awaiting review.

January 2018: Organizers behind a November ballot measure announced that voters will decided whether to automatically restore voting rights for ex-felons, except for those convicted of murder or sex crimes. It needs at least 60% approval.

March 2018: A federal judge issued a scathing ruling that ordered the state to establish “robust and meaningful” new rules to determine when and how to restore ex-felons' voting rights. In February, the judge said the current "unconstitutional" process unfairly relies on the personal support of Scott.

April 2018: Facing a looming deadline, Scott called an emergency late-night meeting Wednesday with board members to consider new rules. But it got cancelled after the Atlanta-based 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals sided with him and ruled he doesn't have to immediately overhaul the process. The suit to overturn the ban was filed in March of last year.

The big picture:

Felon voting rights restoration has the potential to shift the makeup of the country’s largest battleground, which plays a deciding role in presidential elections.

- Observers said Democrats would largely benefit because the prohibition disproportionately affects African-Americans, a group that overwhelmingly votes Democratic. In Florida, per the Sentencing Project, more than 1 in 5 African-Americans are affected.

This story has been updated to reflect news developments.